People have different, strong intuitions about the fundamental nature of reality. I find the intensity of these convictions, and their variety, interesting. (More interesting than the metaphysics itself, actually. I think metaphysical questions are a school of red herrings.)

Here, I suggest a way that neuroscience and Buddhist meditation might help understand why a particular kind of metaphysical disagreement occurs. The experiment I have in mind also involves zombies, so it seems to belong here. Oh, and by the way, it might also explain consciousness.

One area of violent metaphysical disagreement is the mind-body problem: what is the relationship between subjective experiences and the brain?

Philosophical zombies (p-zombies) are hypothetical people who have no experiences: no subjective life. This possibility helps understand the mind-body problem. (If you are unfamiliar with p-zombies, you might want to read “A philosophical zombie” before continuing here.)

Philosophers mostly believe there are no p-zombies. However, some believe that we are all p-zombies, because “subjective experiences” don’t really exist.

There’s another possibility: that only some people are p-zombies! Is it possible that we could find objective ways to test for zombiehood? Could it be that the philosophers who believe we are all p-zombies are, and most people aren’t?

These ideas may sound absurd; but I’ll suggest reasons to think they are possible, and perhaps not even wildly unlikely. In fact, I think I may once have been a p-zombie myself! I will also suggest that zombiehood may be a matter of degree; if so, total zombies seem more likely.

Differences in experience

Most people assume that everyone else has the same experience they do; but this is wrong. Large differences in experience are common, but mainly pass unremarked. For example, my girlfriend discovered only recently that not everyone shares the synesthesia she has always experienced. It came as a surprise that most people don’t experience numbers as having specific colors. I can’t imagine what that would be like, any more than I can imagine what it is like to be a bat.

Therefore, if (say) one in a thousand people is a zombie, they may not even notice that they are different. Or, it may never occur to them to mention it. Or, they may assume that talk about “experience” is a silly social convention one has to go along with. Much everyday talk is social fiction, so why not this? An interesting analogy: psychopaths are unable to experience empathy. They believe that everyone else is the same way, and that all claims of ethical experience are lies. They learn as children to produce “the same lies” themselves, to avoid punishment.

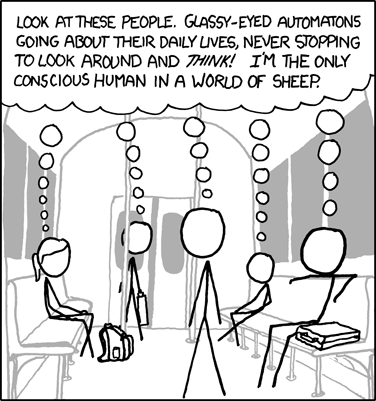

Mind you, the one-in-a-thousand estimate might be backward:

Degrees of zombitude

The intensity and vividness of experience varies. Periods of mental fog are common, when short on sleep, or depressed. At such times, everything seems “gray.” This is not literally a vision problem; instead, the volume knob on all of experience is turned down. At such times, you may encounter depersonalization (you feel like there’s no one home) and derealization (nothing seems real). You may be able to function mostly normally, but your action seems “mechanical.”

It’s quite common then to say “Jeez, I’m a zombie today!” Perhaps we should take this half-joke seriously. Maybe p-zombitude is a spectrum, and you have moved from normal toward the p-zombie state.

A common effect of Buddhist meditation is increased clarity and intensity of experience. All experiences—perceptions, emotions, thoughts—seem “brighter.” You feel “more alive” than usual. Perhaps this is an anti-zombie state: a move in the opposite direction from zombiehood.

Total zombies

If the intensity of experiential vividness is variable, is there any reason it couldn’t go to zero? Could you still function if it did?

I once suddenly “came to” in the middle of a computer science class. Not unusual—except that I was the one teaching it, and had not been asleep! As far as I could tell, I had been a p-zombie for the past couple minutes. There was no conscious experience during that period.

This could be highly embarrassing! Perhaps I had started drooling and groaning “BRAAAAAINS”?—but my students seemed as bored as ever. There was no sign they noticed anything odd happening. The stuff I had written on the whiteboard was no more incoherent than usual.

This is anecdotal evidence only. My belief at the time was that I had lost consciousness, and continued teaching more-or-less normally; but that may have been wrong. For example, I might just have suddenly lost the memory of having been conscious. Still, this makes me more sympathetic to the possibility of total zombies.

This has only happened to me once. I’d be very interested to hear if anyone else has had similar non-experiences! (Please leave a comment, below.)

Possibly related is the Cotard delusion, which means believing you are dead. It is usually associated with depression, depersonalization, and derealization, which all seem like semi-zombie states. Perhaps when those go to the limit, you become a total p-zombie. You realize that you have lost some important mental quality, and the best sense you can make of it is that you have physically died.

Most people think p-zombies aren’t possible because you couldn’t function if you had no conscious awareness. But I don’t see any strong reason to believe that. Familiar types of loss of consciousness (fainting, falling asleep) totally prevent function; but maybe not all do.

Detecting zombies

If there are p-zombies, maybe we can find some. Maybe that would be useful for them. (They could form support groups, for instance.) It also might illuminate some classic problems in philosophy and psychology.

There are several species of p-zombies, whose existence would have different implications. One famous type is the zombie doppelgänger. That is a perfect copy of a “normal” person, which doesn’t have experiences, despite being physically identical. In fact, there are no such duplicates, and even if there were, by definition their zombitude would be undetectable by physical means.

I’m interested in less exotic p-zombies: just regular people who lack experience. So, how could one locate them?

Maybe one could just ask! If you know you are a p-zombie, you could leave a comment below. I’d be interested to hear how you figured it out, and whether it causes you any difficulties. (I’d also like to ask “and what is it like?” but by definition there is no what-it-is-like to be a p-zombie!)

I started this essay by suggesting that metaphysical disagreements might be rooted in psychological differences. Here’s a possibility: eliminative materialists, who believe we are all p-zombies, over-generalize their own lack of experience onto everyone else! In other words, they are p-zombies, and most other people aren’t. Or, perhaps at least they have an atypically low intensity of experience—they are semi-zombies—and therefore find experience uninteresting and unimportant.

Daniel Dennett’s famous eliminativist manifesto, Consciousness Explained, seems, strangely, never to discuss its supposed topic at all. (Many people think Consciousness Ignored would be a more accurate title.) Could it be that he doesn’t realize he has no idea what people are talking about when they speak of subjectivity, because he has none?

So, one approach to zombie-hunting would be to try to find objective differences in brain function between eliminative materialists and people who strongly believe in subjective experience. The modern tool for this is fMRI (“brain scans”).

fMRI can reveal differences in brain connectivity between groups. For example, synesthesia involves extra connections to part of the brain responsible for vision. Psychopathy involves lack of connection between a part of the brain that perceives harm to others and one that processes one’s own emotions.

Eliminative materialists suggest that “awareness” or “experience” is really just one part of the brain registering what is happening in another part. It’s a type of self-monitoring. If so, it could be that p-zombies have weaker connections of that sort than other people do.

The f in fMRI is “functional.” When you scan someone with fMRI, you get them to perform a particular mental task, and the machine shows what parts of the brain they use.

Eliminative materialists function fairly normally. If they are zombies, we’d expect, for most mental tasks, that they’d show the same results as other people. What task would reveal the difference?

Meditation as a zombie test

In one type of Buddhist meditation, you turn awareness on itself. You pay attention not to specific perceptions, emotions, or thoughts, but to the space of awareness in which experience occurs. This task ought to be impossible for p-zombies! It also produces the “anti-zombie” state of heightened experience.

And, similar meditation methods produce distinctive signs in fMRI! I don’t know whether this specific type of meditation has been tried, but I’d be surprised if it didn’t produce a strong fMRI signature.

So, here’s the experiment. Gather a group of eliminative materialists, a matched group who strongly believe in subjective experience, and a random control group of non-meditators. Teach the meditation method to the first two groups. Then run fMRI with all three groups attempting the practice, and see if you see differences. P-zombies vs. untaught controls should show the opposite result from non-zombie meditators vs. controls.

There are several problems. P-zombies may refuse to cooperate. But, it seems that eliminative materialists ought to be enthusiastic about participating, because the biggest problem for their theory is finding a scientific account of awareness. Being able to compare function in aware and unaware—or more and less aware—people might lead directly to a naturalistic explanation.

P-zombies ought also to be unable to follow the meditation instructions, which should make no sense. But then, that might then be a low-tech zombie test; no fMRI needed! Perhaps anyone who can’t understand the instructions is likely to be a zombie.

Anyway, this is a quite preliminary experimental design. I’m suggesting it to provoke discussion.

Does it make sense? Does it seem worth pursuing?

Other metaphysical predispositions

Generalizing the approach, could other metaphysical “intuitions” result from individual mental traits, rather than rational considerations? It is certainly mysterious where they do come from, since they are so strong, contradictory, and ungrounded in evidence.

Philosophical Idealists, for instance, seem to have exceptionally high openness to experience, whereas dualists are typically the opposite. Physicalism seems to correlate with autism spectrum disorder. And so on.

There may be a vast open space for research here…